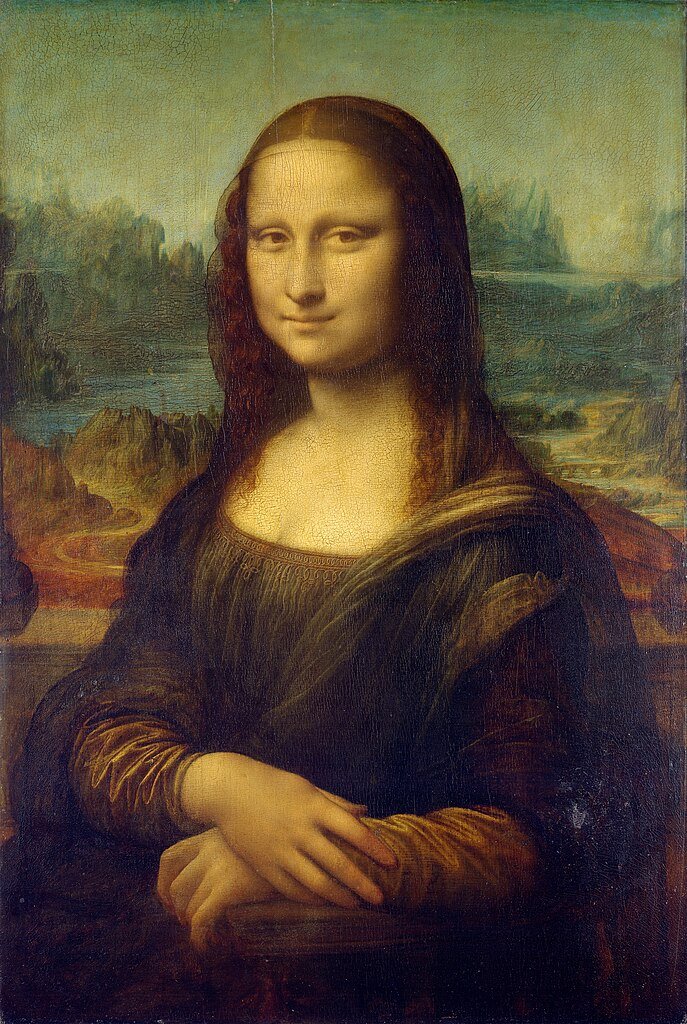

On Jan. 28, activists from the environmental group Riposte Alimentaire (Food Response) tossed soup at Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” to protest the state of the French agricultural system.

The painting 1503-06, poplar on panel), which hangs behind bulletproof glass in the Musée du Louvre, was unharmed and guards soon restored order.

This isn’t the first time the painting has been attacked nor is it alone in its appeal to climate activists looking to make a statement. Their point seems to be we care more about art than the environment. But is that a valid point?

The median household income for American farmers is around $95,000 — about $35,000 more than the median household income for artists. I can also tell you anecdotally as a longtime cultural writer — one who has lost a couple of jobs — that the arts continue to be viewed as an extra, a frill, something that is not particularly useful, relevant or relatable, particularly in the digital age. Oh, yes, contemporary art may have a place at auction. But Old Masters? Forget it.

So what are climate activists so exorcised about? It’s not as if they would be any better off if the “Mona Lisa” had never existed. Much art is about the environment. (Indeed, there’s a whole genre called environmental art.) Many artists support the environment and are even activists themselves. So why turn off the choir you’re actually preaching to? Why make a false equivalence between art, which society is increasingly less educated in anyway, and the state of the environment we’re all doing precious little about? Why create a false dichotomy between art and nature, which have always gone hand in hand in landscape painting?

Why feed the notion — pun intended — that only the utilitarian is important? What about those things that feed the soul, that matter in and of their own sake, not because they “do” anything?And whose art is it anyway? If it belongs to all of us, what about those of us who would rather gaze on it than listen to some strident protester?

When I think of art and food, I think not only of all the artists I’ve written about who’ve used food in their work but about one of my favorite novels, Edna Ferber’s 1925 Pulitzer Prize winner “So Big.” It tells the story of schoolteacher Selena Peake De Jong, who must take over the family farm and make a life for herself and son Dirk after her husband dies. Along the way, Selena had encouraged the artistic interests of Rolf Pool, whose family lives on a neighboring farm in their Illinois community.

Early in the book, Ferber sets out the theme that there are two kinds of people — wheat, those who produce useful things like food, and emeralds, those who produce art. Dirk, an architect turned stockbroker, rejects both, only to lose the artistic woman he loves, Dallas O’Mara, to Rolf in the process.

Ferber doesn’t say wheat is superior to emeralds but rather than there is both a workmanlike quality and a beauty to each — as opposed to making money your god, as Dirk does.

There’s enough divisiveness in this world — fueled in part by people who are only interested in ratings, money, influence and power. Putting art in competition with the environment furthers neither.