In “The Age of Innocence,” novelist Edith Wharton’s 1920 Pulitzer Prize-winning “backward glance” at the Gilded Age New York of her childhood, lawyer Newland Archer is set to marry May Welland in a match of illustrious families. The couple’s prospective marital bliss is soon clouded, however, by the New York return of May’s cousin, the beautiful, independent-minded Countess Ellen Olenska, seeking to escape her unhappy union with a Polish count.

Newland is asked to dissuade Ellen from the scandal of divorce — in Martin Scorsese’s 1993 film adaptation, he’s asked to facilitate the divorce on her behalf — but instead falls in love with her and particularly her unconventionally view of society, both of which threaten its norms. What transpires are the efforts of everyone — the honorable Ellen; Mrs. Manson Mingott, the family’s redoutable matriarch; but especially May, who turns out to be less demure and more devious than expected — to ensure that Newland remains in the marriage’s, and society’s, folds.

I thought a lot about “The Age of Innocence” as I binge-watched the fifth season of “The Crown” — even as the sixth and final season concluded on Netflix — and read about the ouster of Claudine Gay as president of Harvard University after her disastrously naive performance before a Congressional committee on anti-Semitism on college campuses in the wake of the Israel-Hamas war.

First to “The Crown,” whose fifth season is much taken up with the unhappy marriage and inevitable split of Prince Charles (now King Charles III) and his first wife, Diana, Princess of Wales. A lot has been made about the historical accuracy of the series, which viewers should immediately understand is a dramatization not a documentary. Those of us who covered the “War of the Waleses,” however, will recognize familiar ground as 1990s headlines come to life.

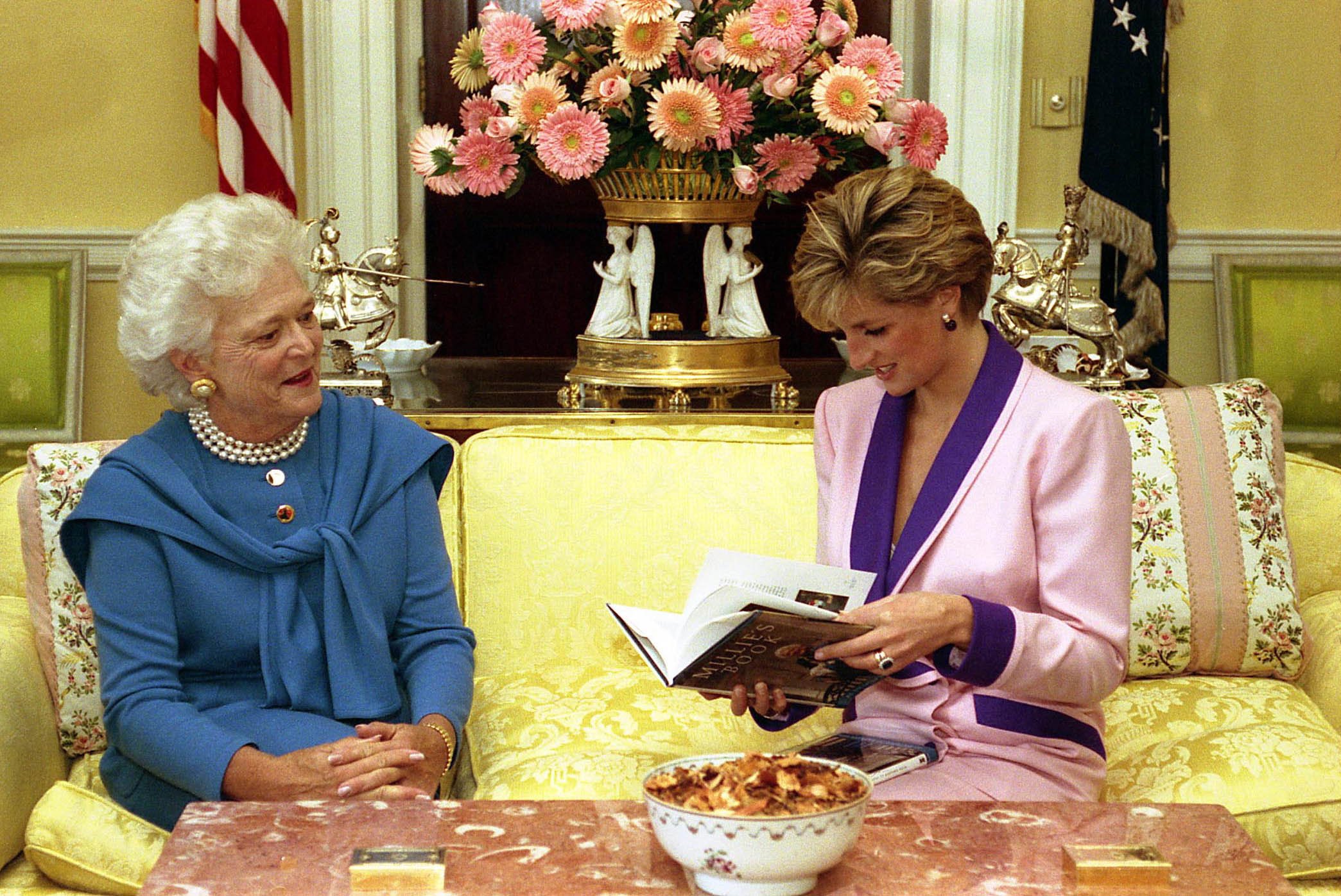

Casting its own backward glance on events some 30 years past, “The Crown” offers the not entirely fresh insight that much of society — much of culture, much of history — is about the sacrifice of the individual who bucks convention for the good and advancement of the group. Had the late Princess of Wales turned a blind eye to her cheating spouse and not gone on to a series of equally fruitless, public romantic relationships, culminating in her fatal encounter with Dodi Fayed, she might be alive today. But her quest for love transcended her ability and willingness to play by the rules. (She wasn’t the only one. Queen Elizabeth II’s sister, Princess Margaret, forefeited her relationship with divorced Group Capt. Peter Townsend to marry and divorce photographer Anthony Armstrong-Jones, Earl of Snowdon, and die at age 70 after a series of strokes brought on by drinking and smoking.)

There’s a chilling scene in season five that rings especially true: The queen’s husband, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (played with real bite by Jonathan Pryce), whom the queen deferred to in family matters, counsels Diana (Elizabeth Debicki, who superbly captures the princess’ voice and mannerisms, adding a sharp, self-deprecating wit), to seek satisfaction elsewhere within the social constraints of the family. For Philip, that meant carriage driving and, as “The Crown” depicts, a relationship with Penny Knatchbull, the Countess Mountbatten of Burma (the enchanting Natascha McElhone), whom Philip persuaded to take up carriage driving after the death of her 5-year-old daughter, Leonora, from kidney cancer.

For Diana, there would be no carriage driving, nothing that could salve her shattered heart within the confines of the tribe. And make no mistake about it, society — particularly on that exalted plane — is a kind of tribalism. It’s seemingly incongruous but not surprising that the Scorsese of “Mean Streets” and “Goodfellas” fame would make “The Age of Innocence”: Society, like the mob, operates by a brutal code of conduct. So instead of carriage driving for Diana, there would be other men in the driver’s seat, leading to the fatal 1997 crash in the Paris tunnel.

And what of Gay, the ousted Harvard president accused of plagiarism after she failed in a Congressional hearing to denounce campus anti-Semitism and calls for Jewish genocide, instead offering a smug ,academic response about “context” in a situation that didn’t call for it? Was this Black woman, a double outsider in academe, thrown to the wolves to preserve the Harvard tribe? Some see it as an attack on the DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion) standards of academia and corporate America that the right condemns as “woke.”

But I think Gay being a Black woman is a double red herring here. Had her performance — and a public appearance in politics is as much a performance as it is in the arts — not been so maddeningly stupid, the separate plagiarism charges might never have surfaced. You think of what President Richard Nixon, brought down by Watergate, said: “I gave them the sword. And they stuck it in.” You can’t be part of a tribe, let alone lead the tribe, and give anyone within or without the tribe a sword to stick in your back.

Queen Elizabeth II, whatever her ups and downs in public opinion, particularly during the Diana years, never gave anyone the sword.

By the way, in “A Feast of Words: The Triumph of Edith Wharton” (Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., 1995), Cynthia Griffin Wolff writes that at the end of the original draft of “The Age of Innocence,” Newland runs off with Ellen, only to leave her. Even in the published novel, he demurs from renewing old acquaintance with her years after his wife dies — for some of us are only comfortable playing by the tribe’s rules.