The deaths of five men in the implosion of the submersible Titan has shown us, as tragedies do, the best and the worst of humanity.

The best could be seen in the herculean five-day transatlantic effort by four nations — Canada, the United States, France and Great Britain — to save lives even as the U.S. Navy detected but could not definitely confirm the implosion on Father’s Day, June 18. The worst was, well, everything else from the foolhardy tour itself to some of the slapdash reporting to the ignorant, often mean-spirited internet reaction.

“These men were true explorers who shared a distinct spirit of adventure, and a deep passion for exploring and protecting the world’s oceans,” OceanGate Expeditions, owner and operator of the vessel, said in a statement. “Our hearts are with these five souls and every member of their families during this tragic time.”

Appropriate, compassionate sentiments, perhaps, but not entirely accurate. They weren’t all explorers, and they certainly weren’t discovering new worlds. They were rich adventurers who in some cases paid $250,000 a person to be hauled down to the remains of the RMS Titanic, much like rich people who’ve paid to be hauled up Mount Everest by sherpas or rich people who will be hauled on rockets into space. Technology and money have trumped critical thinking and true humility (the knowledge of our strengths as well as our weaknesses) in our society. Instead, we get hubris: I have a mike, so I’m a singer. I have a camera, so I’m a director. I have a computer, so I’m an influencer or, God help us, a writer.

We live in a world exemplified by Titan pilot and OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush where people confuse recklessness with visionary risk-taking and lack the four Ts to hone a craft — talent, training, technique and the right temperament for the other three. It’s all about shortcuts to the top. The result was an unregulated vessel that was not seaworthy and the deaths of five people — Rush, 61, Hamish Harding, 58, a British explorer; Paul-Henri Nargeolet, 77, a French maritime expert who had made more than 35 dives to the Titanic; Shahzada Dawood, 48, a British businessman; and his 19-year-old son, Suleman Dawood, a university student.

This kid, according to his aunt, only went to please his dad on Father’s Day. That hardly sounds like someone who was passionate about exploration and oceanic conservation. If you want to conserve the earth’s resources, would you be rushing around the world adding to a large carbon footprint?

That these were rich people who boarded a vessel that took shortcuts to see a vessel that took shortcuts to cross the Atlantic, causing other rich people to perish, was not lost on the internet. (Perhaps not so coincidentally Rush’s wife, Wendy, is the grear-great-granddaughter of Isadore and Ida Straus, who perished when the Titanic sank on April 15, 1912.) Having said all this, that doesn’t mean we don’t mourn them. These were human beings. They made a mistake that crushed the life out of them. In such instances, you don’t know what hit you. Death is instantaneous. Thank God. May they rest in peace.

The internet, however, couldn’t let it go. There was endless stupid commentary about how much this was costing taxpayers, as if you wouldn’t try to rescue people; about killer whales, which do not prey on humans and have nothing to do with this story; and the U.S. botching the investigation by refusing to let the British help, apparently based on false British newspaper reports; along with virtue signaling about the comparative lack of interest in the appalling deaths of hundreds of migrants off the coast of an allegedly indifferent Greece.

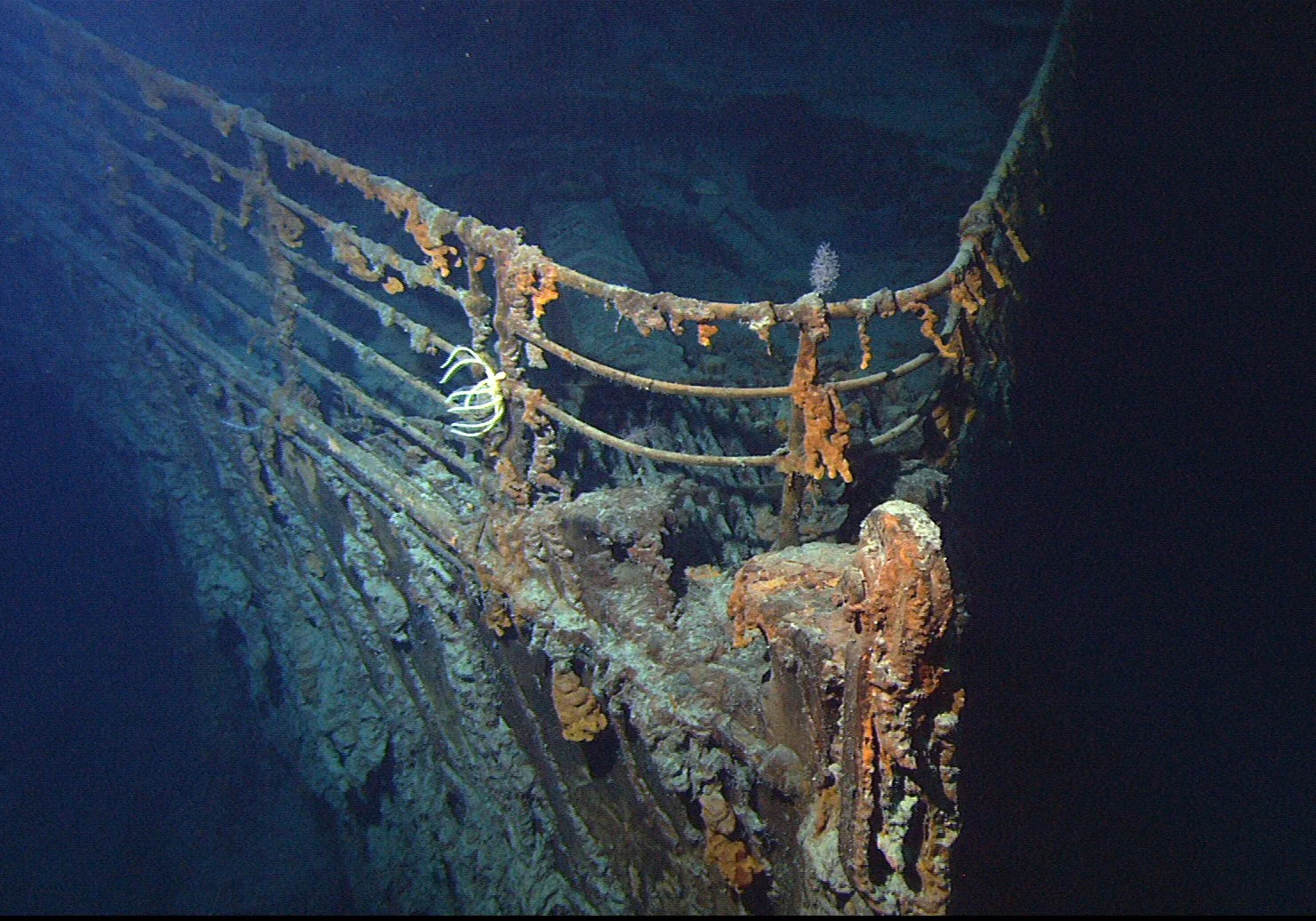

It’s not that the submersible story is more important, because of the wealth involved. Both stories have been covered and will continue to be followed. But it’s easier to wrap your head around the deaths of five people than 500. The migrant story is a continuing, amorphous crisis with no practical solution in sight. The Titanic is a story whose fascinating narrative arc was complete, buried in time on the ocean floor for us to contemplate at a safe distance.

Or so we thought.