Wednesday, Nov. 22 , marks the 60th anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy by Lee Harvey Oswald in Dallas.

Those of a certain vintage can remember where they were and what they were doing when they heard the shocking news. In a sense, we’ve never recovered from it.

Perhaps that’s why JFK — like many cultural figures who have captured their times, including Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley – has gone on to a rich afterlife in this world. Part of this was the creation of his widow, Jacqueline Lee Bouvier Kennedy Onassis, who planted the seeds for a comparison between the Kennedy Administration and Camelot, a noble but fleeting ancient British kingdom immortalized in poetry and a hit Broadway show, with historian Theodore White soon after the assassination. Part of it is because the Kennedy family’s long history of public service – and tragedy – continues. Robert F. Kennedy Jr., son of JFK’s slain brother, is following in their political footsteps by running for president, although the vaccine-skeptical environmental lawyer has proved an even more controversial figure.

But most of JFK’s afterlife has to do with our desire to hold on to him and his family. (That’s what Halloween and horror movies get wrong: It is the living who haunt the dead.) I recently wrote about Chappaqua children’s librarian and author Ronni Diamondstein’s debut work, “Jackie and the Books She Loved.”

“CBK: Carolyn Bessette Kennedy: A Life in Fashion,” published Nov. 7, explores the continuing influence of her minimalist, monochromatic style on fashion – and reminds us of the youthful promise that was extinguished when the fashion publicist; her husband, John F. Kennedy Jr.; and her sister Lauren Bessette were killed in a plane crash off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard on July 16, 1999.

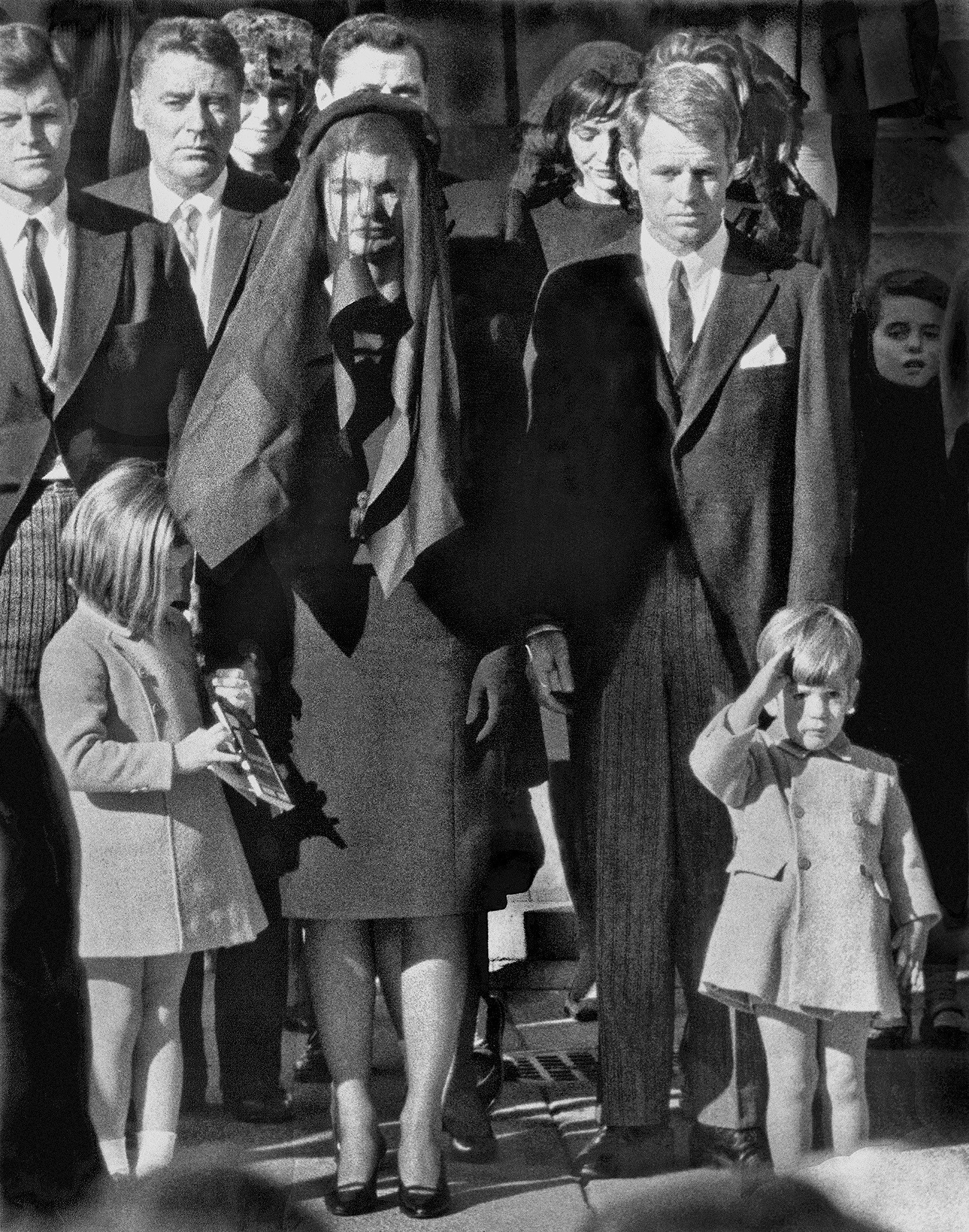

From Dec. 9 through April 7, The Capa Space in Yorktown Heights, New York, will present “American Moments: John Shearer,” an exhibit of more than 30 photographs by the late Katonah, New York, resident, who at age 17 took a poignant photograph of 3-year-old John F. Kennedy Jr. saluting his father's casket, despite the photographer being knocked down by Secret Service agents. This propelled Shearer's career in the 1960s and ’70s as one of the few Black photographers at major publications like Life and Look magazines – a career that would see him leverage that unique vantage to cover the civil rights movement.

In a culturally and politically divided time, we hold on to those touchstones that remind us of when we were young and loved; when leaders were apsirational and inspirational; when life, like a summer road, seemed filled with endless possibilities. In Dallas, we learned once again the illusion of those possibilities.

And yet, we hold fast to the memory of a time when we thought we were great – and the possibility that we can think so again.