Sandy Koufax’s 1962 Bell Brand baseball card

When I was a child, I raced home one day from school to turn on the TV to see a 20-year-old pitcher who would soon become a favorite, Jim Palmer of the Baltimore Orioles, outduel Sandy Koufax of the Los Angeles Dodgers in Game 2 of the 1966 World Series. It wasn’t even close. Dodger centerfielder Willie Davis lost two fly balls in the October sun and the Dodgers, defending Series’ champ, went down 6-0, losing the series in four straight.

It was the last game Koufax ever pitched for afterward he announced his retirement from baseball, having battled traumatic arthritis along with the drugs that kept it at bay for a number of years. He was just 30 years old.

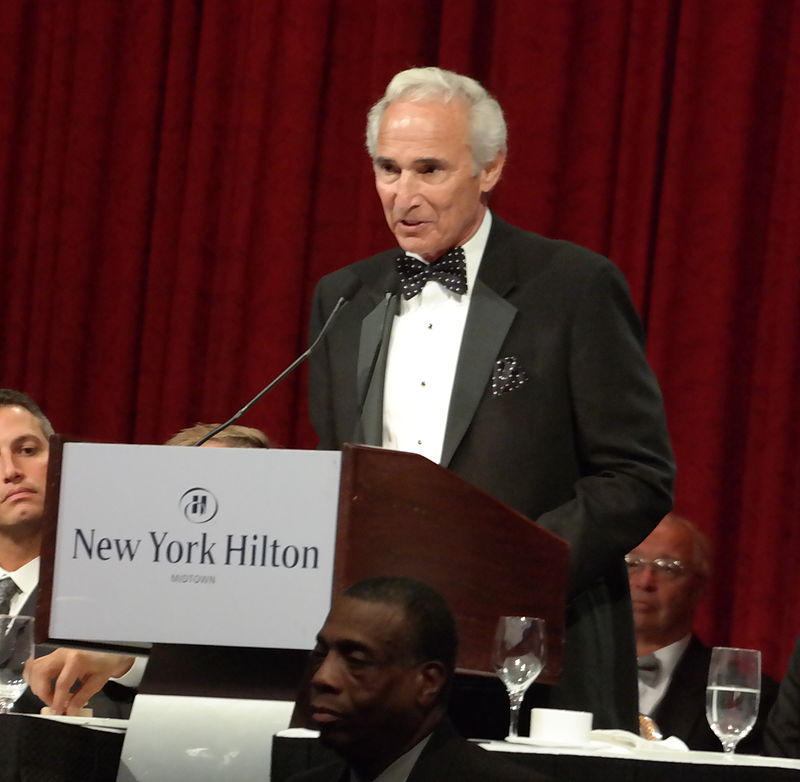

Sandy Koufax at the Baseball Writers’ Association of America dinner in 2014. Photograph by Arturo Pardavila III.

But brilliance often comes in short bursts. Sandy Koufax was the greatest ballplayer I have ever seen – the Rod Laver of baseball, or maybe Laver was the Sandy Koufax of tennis. And like Laver, who was also a lefty, he had the Herculean feats to lay claim to immortality. The four no-hitters, including the perfect game against my Cubbies; the trim ERA; the pileup of strikeouts per game (as one of only four Hall of Fame pitchers to have more Ks than innings pitched); and the command of a repertoire of pitches that had sportswriters reaching for comparisons not to other pitchers but to Renaissance artists.

That’s what made him a great pitcher. What made him a great player was something else, something that was harder to quantify. He had the greatest concentration of anyone I’ve ever seen. His ability to stay in the moment, to bore down on a hitter and shut out almost everything else (for he did have to keep the occasional base runner in mind) was unsurpassed. I always said I learned everything I know about focus from Koufax. Indeed, I probably owe him both my scholastic and writing careers.

But his focus was, I soon realized, tied to his unwillingness to be defeated. He simply refused to be anyone but the last man standing. You had to beat him. He never beat himself.

All of this was born of a kind of American originality we associate with such icons as Muhammad Ali, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Marlon Brando. A Jew, Koufax would never pitch on Yom Kippur, not even in the World Series. He stood up for what he believed was his due – and that of his teammates – in an era in which you kept your head down and your mouth shut.

Koufax always reminded me of Robert E. Lee Prewitt in James Jones’ “From Here to Eternity,” who says, “A man don’t go his own way, he’s nothing.”

The price of that individuality is borne out in Michael Leahy’s new book “The Last Innocents: The Collision of the Turbulent Sixties and the Los Angeles Dodgers” (HarperCollins Publishers, $26.99, 473 pages). The book is not without its flaws. It is repetitious in its worshipfulness – or should that be worshipful in its repetition? (As much as I admire Koufax, I as a reporter have never had any patience with people in public life like him who guard their privacy to the point that they won’t be interviewed, or they’ll only be interviewed on certain topics or when they want to use you.)

But “The Last Innocents” is a gripping portrait of a paternalistic workplace that still defines America and whose venality has come home to roost in the bitterness of the current presidential campaign. It’s the kind of workplace I grapple with in my forthcoming football novel “The Penalty for Holding,” which will be published next year by Less Than Three Press. I worried that its portrayal of a capricious owner, a sadistic, racist coach, players who were both defiant and too eager to please and a star who pushes himself beyond the limits of human endurance was over the top. But after reading “The Last Innocents” – which is about a time before unions and free agency leveled the playing field – I realized you can’t make this stuff up. And that it still resonates today.

Though the Dodgers deserve credit for providing the setting for Jackie Robinson to break the color barrier in 1947, they operated, according to Leahy, in the manner of other teams and American companies. The Dodgers took care of you in the way they wanted to take care of you. In return, you did your job, accepted the salary you were offered and the opportunities that came your way. You didn’t ask for more. Indeed, you didn’t rock the boat, because to do so was to be disloyal to the “family” that was the team and because the America of the 1960s was an incendiary mess.

Leahy is at his best portraying the efforts of black stars like the speedster and shortstop Maury Wills, outfielder Tommy Davis and catcher John Roseboro to ride the wave of political change. There is a poignance in Wills’ giddiness at being free to eat in the hotel restaurants that formerly served whites only and a poignance in Roseboro continuing to order room service to avoid those restaurants. Some people have been caged so long that they continue to build cages where none exist.

Being white, Koufax didn’t have it as bad as the black players. No woman told him he couldn’t use a laudromat as one once told outfielder Lou Johnson. But as “Super Jew” – as his teammates affectionately called him in a politically incorrect age – Koufax was more than a black man but less than a white one. Held at arms’ length by an aloof coach (Walter Alston) bemused by the pitcher’s self-possession, portrayed by certain sportswriters as a stereotyped intellectual money-grubber, alternately lionized and demonized by fans, Koufax charted his own course out of desire and necessity – holding out with fellow pitching star Don Drysdale for more money and fighting for every start, every inning on the mound to the point of injury.

Maybe he had an inkling that his time in baseball would be as brief as it was brilliant.

In later years, he would flirt with public life, turning his back on a broadcasting career but showing up as a spring training coach or to play golf in tournaments benefiting Joe and Ali Torre’s Safe at Home Foundation.

He married twice – his first wife was movie star Richard Widmark’s daughter, Anne – but he had no children. And that, too, is somehow fitting.

Some people are simply one-in-themselves.