The controversy over the faceoff between “Fearless Girl” and “Charging Bull” on Wall Street has raised all sorts of psychosexual and political implications.

Some have seen the 4-foot-girl – hands on hips, chest puffed like a sail heading into the wind – as a symbol of feminist ideals. Apparently, that’s what sponsor State Street Global Advisors, which wants to encourage more women in the boardroom, had in mind.

For New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, it’s a cautionary work about “unfettered capitalism.” OK, Bill, you might want to go back to the drawing board on that one.

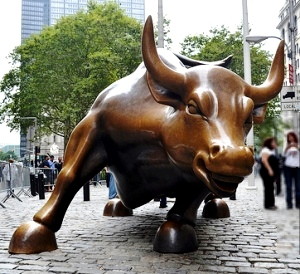

But “Charging Bull” creator Arturo Di Modica – who fashioned the work in 1987, a year in which the market crashed, and spent his own money to have the 7,000-pound sculpture placed in the financial district – has reacted the way any man does when confronted with a powerful woman, and this one a slip of a girl at that. “It’s really bad,” Gail Collins quotes him as saying in her Saturday New York Times column.

I say that when you place a sculpture in a public space – the New York Stock Exchange didn’t want it in front of its building, so the Ed Koch Administration moved it to its current home, the adjacent Bowling Green – you take your chances. Time and cityscapes change. (The French gave the Statue of Liberty to the United States to mark the resolution of the Civil War. The immigration interpretation came later.) New sculptures are added, creating a different dialogue and a fresh context and perspective. Cowboy up, Arturo. And look at it this way: At least you weren’t one of the women molested at Choate Rosemary Hall.

But I see another interpretation. “Fearless Girl” reminds me of the legend of Ariadne, the equally fearless daughter of greedy King Minos, who required that sacrifices – no doubt of the nubile female virgin type – be made to the Minotaur, the half-bull, half-man waiting at the end of an elaborate labyrinth. Ariadne was in charge of the labyrinth, but she would team with the antihero Theseus to venture within, kill the Minotaur and spare the sacrificial victims. (Martha Graham would turn this a ballet about a young woman’s sexual awakening and fears – of course, she would – in “Errand Into the Maze.”)

Ariadne has been the subject of many artworks, for her involvement with Theseus, just like Medea’s with Jason, would not end happily ever after. (Indeed, these women are like the nurses and secretaries who helped the hubbies rise only to find themselves abandoned for the newer model in the form of the second wife.)

Theseus abandoned Ariadne on the island Naxos, where she was rescued by the hunky god Dionysus (because, of course, men always think women need to be rescued by them). It’s the subject of the magnificent hammered bronze Hellenistic “Derveni Krater” that I saw at the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki last summer and Richard Strauss’ opera “Ariadne auf Naxos.”

But that, as they say, is another story.