Image here

“Only in America could a conversation about racial oppression devolve into one black millionaire calling out a biracial millionaire for not knowing what's it's like to be truly oppressed.”

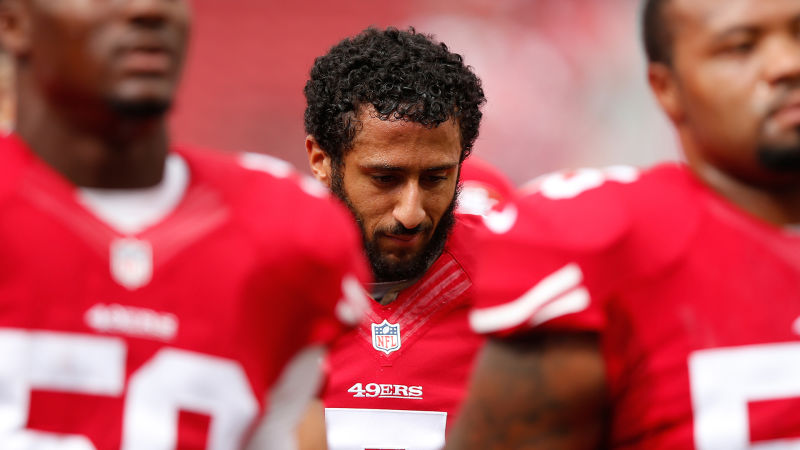

So posted Mark Thomas on an ESPN thread about NFL analyst Rodney Harrison criticizing San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick after he sat through the National Anthem in a preseason game to protest violence toward blacks and other people of color in this country. Harrison said that Kaepernick – whom all eyes will be on when the Niners take on the San Diego Chargers on CBS’ “Thursday Night Football” – didn’t know what it was like to be a black man.

"I tell you this, I'm a black man. And Colin Kaepernick – he's not black," Harrison said. "He cannot understand what I face and what other young black men and black people face, or people of color face, on an every single [day] basis. When you walk in a grocery store, and you might have $2,000 or $3,000 in your pocket and you go up into a Foot Locker and they're looking at you like you about to steal something.”

Let’s leave aside the fictional person of any color who goes into the grocery store or Foot Locker with thousands of smackeroos – for what, every lottery ticket there is? One heckuva pair of sneakers? Harrison later apologized, saying he didn’t realize Kaepernick was “mixed race.” (Kaepernick is the natural child of a white mother and a black father and was adopted by a white family.) But Harrison’s ignorant initial comments – compounded by an awkward apology – raise an intriguing question: What does it mean to be black or part of any race?

The word “race” is a social construct. This from Wikipedia in its “race” entry:

“There is a wide consensus that the racial categories that are common in everyday usage are socially constructed, and that racial groups cannot be biologically defined.”

It bears repeating: Blacks are no different than whites, Asians, Hispanics, American Indians. We are the same biologically.

Race then is cultural and the definition has shifted over time. At first, race was defined by common language, then by common country. In this sense, Alexander the Great was “mixed race,” as his mother was from Epirus, and thus northern Greek, and his father, Macedonian. Only in the 17th century did race come to be defined as we define it still, as a series of physical characteristics. One of the things that is particularly loathsome in the discussion of the Kaepernick protest and “blacklash” – which have spun way beyond the actual protest – is the criticism from some black posters that he isn’t black enough because of the hair, bone structure and light brown skin that have led other posters to suggest that his father must’ve been North African, that is, Arab and/or Muslim. (On the other hand, some black women in other contexts have referred to his features admiringly as white chocolate.)

Clearly, to be of the half and half, to belong to two worlds is to belong to neither – as I discuss in my forthcoming novel “The Penalty for Holding,” about a gay, biracial quarterback’s search for identity in the NFL.

Your race, then, is defined not just by how you see yourself but how others see you. And that can be sadly limiting.

Here’s Michael Siciliano’s post on the same thread:

“I'm a professional writer. I have a very vivid and active imagination. I'm also Caucasian. However, I think I've read enough and heard enough about the black experience in America to understand. How the hell does (Rodney Harrison) know that no white person could understand what daily bigotry is like?”

Siciliano goes on to consider the plight of white women, white Jews, white gays.

“Bigotry is awful. It's vile. African-Americans deserve to live in a country where skin tone makes absolutely no difference. But don't tell me I can't possibly understand what it's like. I empathize. Don't toss that away.”

No, don’t.