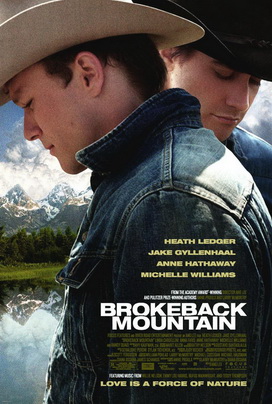

The iconic “Brokeback Mountain” movie poster may have been inspired by the poster for “Titanic” and was in turn the inspiration for a New Yorker parody cover featuring President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney.

When people ask me to give them the “elevator pitch” for my novel “Water Music,” I always say it’s “‘Brokeback Mountain’ meets ‘Fifty Shades of Grey’” – not because I would equate my book with those works but because it deals with gay lovers and issues of power and submission. Such is our world – with no time for anything – that we must reduce everything to labels, boxes and clichés.

Everyone who writes about gay men in love today owes a debt, however, to Annie Proulx’s sparely beautiful short story about two 1960s cowboys – shepherds really – whose love is doomed by an inability to communicate, by a closeted world and, in a sense, by the all-consuming nature of that love.

Now Proulx’s short story and Ang Lee’s equally haunting film version – starring the late Heath Ledger as Ennis Del Mar, the more constricted of the two lovers, and Jake Gyllenhaal as Jack Twist, the more expressive – have been turned into an opera by Charles Wuorinen, whose atonal style would seem pitch-perfect for Proulx’s Heminway-esque writing. (She contributed the libretto for the work, which premieres Jan. 28 and runs through Feb. 11 at the Teatro Real in Madrid.)

Tom Hiddleston, whose Prince Hal and Loki are the subjects – or objects – of homoerotic fan fiction. Photograph by Sachyn Mital.

In a marvelously titled report for the Jan. 26 Sunday New York Times, “Love That Dare Not Sing Its Name,” Zachary Woolfe notes that the 2005 film “appeared on the cusp of a new era in gay rights and gay representation.” Proulx’s story, which was originally published in The New Yorker in 1997, follows in the venerable tradition of women writing homoerotic works (Mary Renault’s novels of ancient Greece and Alexander the Great, Patricia Highsmith’s “Ripley” novels). It’s a small group but a growing trend. Google such sites as Live Journal or Archive of Our Own and you’ll find stories in which Shakespeare’s Prince Hal, as incarnated by the dishy Tom Hiddleston, is in love with Chris Hemsworth’s Huntsman from the film “Snow White and the Huntsman,” or Robert Downey Jr. is having an affair with his “Sherlock Holmes” co-star Jude Law or Michael Phelps and Ryan Lochte are married or Roger Federer is either sleeping with Rafael Nadal or engaged to Novak Djokovic.

Needless to say, there are lots of “Brokeback”-inspired stories, which apparently drive Proulx – who sounds like a bit of a P.L. Travers – nuts. In the same Times’ article, she says, “The final film was – it was what it was. It wasn’t the story that was in the magazine. The film was more poignant and heart-rending, and I think a lot of that was due to the music (by Gustavo Santaolalla), which was perfectly suited to the film.”

Translation: The movie romanticized her brittle-as-a-bramble-bush tale, with its tough-love theme – “If you can’t fix it, you gotta stand it.” But then, movies, by their very visual nature, tend to make everything more beautiful, because they’re organized spatially and have to grab you immediately. Writing, on the other hand, evolves over time. Its devotees are along for the ride, so its characters can unfold leisurely. A case in point: Margaret Mitchell’s Scarlett O’Hara is bewitching but no beauty, but in the classic 1939 film of Mitchell’s best seller she’s played by bewitching beauty Vivien Leigh.

Proulx, of course, is entitled to be irritated by the “Brokeback” “homages.” Lots of so-called fan fiction is gushy and soft-core. It’s not in the class of Proulx’s, Highsmith’s or Renault’s work.

But some of it is wonderful. I can remember reading a story in which Rafa and Nole are lovers. Rafa dies but comes back as a ghost – the author describes him strikingly as looking like a glass teapot – so that Nole won’t be alone. It’s really moving.

Whether literary or not, all homoerotic works written by women beg the questions, How? and Why?

The Why may be easier to answer. Women tend to be more verbal and less visual than men, particularly with regard to sex. (Hence the popularity of romance novels.) So it’s not surprising that women would turn to writing to express themselves erotically. Our post-feminist age and the anonymity of the Internet have also emboldened them sexually. (Remember that “Fifty Shades” began its life as “Twilight” fan fiction.)

Then, too, just as men have gotten off on lesbian sex, women like visiting the foreign country of men-on-men in books and even in film. (Eighty percent of the audience for “Brokeback” was female. And don’t forget those episodes of “Sex and the City” in which the ladies got their jollies watching gay porn.)

The difference is that men use same-sex erotica to engage. They see themselves as part of a threesome.

Women use same-sex erotica to detach. It’s a way to experience subjects that might make them uncomfortable if they were about a male-female relationship, says Ogi Ogas, co-author of “A Billion Wicked Thoughts.”

But there’s something else going on here, a question of control. Note that many of the fan fiction works at least are about characters or real-life men who are heterosexual. They become surrogates for or love objects of the authors, many of whom are young women who idolize these men or characters and would otherwise have no access to them.

As for the How... that’s more of a mystery. I can only say that in “Water Music,” I was interested in writing a story about a group of people trapped in a psychological vise. Gay athletes seemed to fit the bill. And then I just put myself in the minds of these characters – which is what male writers have done in creating women for centuries.

Homoerotica by women is not to every taste. But it is an idea whose time has come. And in the words of “Brokeback,” If you can’t fix it, you gotta stand it.